I want to wish everyone a Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year. I also want to thank everyone for their support and encouragement. This blog is a labor of love for me and the response has been overwhelmingly positive.

I specifically want to thank Jim Gurney, Matthew Innis, Stapleton Kearns and Frank Ordaz, who according to my stats, send me the bulk of my readers; I am truly humbled by their generosity.

I also want to thank my lovely partner Diane who has supported all my artistic endeavors all these years; I couldn't do it without her help.

Best,

Armand

Painting the Sky Color in a Landscape

by Armand Cabrera

By their very nature landscape paintings generally contain mostly land in the division of space in the painting. Usually less than a third of the canvas area is reserved for the sky. This seems to confuse most people when they start painting and they ignore what they see and paint what they think they know. What they think they know is the sky is blue and so it has to be a deep saturated blue in my painting.

This causes problems for the rest of your painting, because the sky, more than anything else is the key to how the light in the painting is behaving. Get the sky color wrong and you ruin the sense of light in the painting. If we examine the area of sky that is actually in the painting we will find for the most part it is made up very little blue if any. The blues that are there tend to be very high key, with lower saturation than at the skies zenith. So what is going on here?

Well, if you measure the relative size of visible sky included in your painting you will find it is barely above the horizon line. All of that blue sky you are looking at has no place in your painting if this is the case. The sky just above the horizon is affected by dust and clouds and rarely presents the deep blue of the zenith. At the lower levels toward the horizon the sky leans toward a greenish blue depending on the meteorological conditions. This is especially true in the summer when the air is warmer and the angle of the sun higher. In winter the lower sun angle and cooler air offer more opportunities for a clear blue sky.

Painting outdoors offers the artist a unique chance to observe these affects firsthand. When painting from nature it is important to leave your preconceived ideas at home and be open to the experience. This is especially true when including skies in your painting.

By their very nature landscape paintings generally contain mostly land in the division of space in the painting. Usually less than a third of the canvas area is reserved for the sky. This seems to confuse most people when they start painting and they ignore what they see and paint what they think they know. What they think they know is the sky is blue and so it has to be a deep saturated blue in my painting.

This causes problems for the rest of your painting, because the sky, more than anything else is the key to how the light in the painting is behaving. Get the sky color wrong and you ruin the sense of light in the painting. If we examine the area of sky that is actually in the painting we will find for the most part it is made up very little blue if any. The blues that are there tend to be very high key, with lower saturation than at the skies zenith. So what is going on here?

Well, if you measure the relative size of visible sky included in your painting you will find it is barely above the horizon line. All of that blue sky you are looking at has no place in your painting if this is the case. The sky just above the horizon is affected by dust and clouds and rarely presents the deep blue of the zenith. At the lower levels toward the horizon the sky leans toward a greenish blue depending on the meteorological conditions. This is especially true in the summer when the air is warmer and the angle of the sun higher. In winter the lower sun angle and cooler air offer more opportunities for a clear blue sky.

Painting outdoors offers the artist a unique chance to observe these affects firsthand. When painting from nature it is important to leave your preconceived ideas at home and be open to the experience. This is especially true when including skies in your painting.

Painting Snow

by Armand Cabrera

Since the first snow storms are here I thought I would throw in some observations for those artists willing to get out and paint in winter weather. Painting snow presents a unique challenge compared to other subjects. The relative brightness of the landscape can hurt your eyes even when the sun is not out, the extreme temperatures can affect more than your comfort and actually harm you if you aren’t smart or careful, and conditions can have an adverse affect on your materials.

Being aware of all these things, you may question why someone would want to paint outdoors in the snow in the first place. For me it is to capture the wonder and beauty the frozen landscape has to offer. Snow is almost impossible to photograph effectively so your only real alternative is to paint it from life. Colors must be organized for maximum effect, compositions carefully thought out and value ranges keyed for each picture.

There are some things about snow you should look for when painting; some of these things are observable but others must use constructive techniques express them in an image. Practice outdoors and trial and error are your best tools for these decisions.

There is always a slight bit of subsurface scattering going on in snow, even on overcast days, this softens transitions between light and shadow and gives the snow a tinge of the hue from whatever local color is affecting it. Where the sunlight hits snow, it spreads out in almost in a prismatic effect, the shadow areas pick up the light of the sky color and reflections from sunlit areas. Because of all of these effects snow is never pure white except where you have a direct highlight from the sun. When you are in a position to actually see the highlights, you quickly realize how much relatively darker the rest of the snow is even in the lit areas.

Different types of snow affect these properties in different ways. Snow that has been melted and refrozen looks and behaves differently than freshly fallen powder. Snow patches appear more contrasted because there is no snow around them. When there is snow everywhere, that snow has a tendency to lighten everything around it with reflected and ambient light lessening the contrast and raising the key of the painting over all. These things are observable and paintable if you are willing to get out, experience it and see it first hand for yourself.

Paintings in this article are, from top to bottom Aldro T. Hibbard,

Fritz Thaulow, Birge harrison, Isaac Levitan, Edward Redfield

Since the first snow storms are here I thought I would throw in some observations for those artists willing to get out and paint in winter weather. Painting snow presents a unique challenge compared to other subjects. The relative brightness of the landscape can hurt your eyes even when the sun is not out, the extreme temperatures can affect more than your comfort and actually harm you if you aren’t smart or careful, and conditions can have an adverse affect on your materials.

Being aware of all these things, you may question why someone would want to paint outdoors in the snow in the first place. For me it is to capture the wonder and beauty the frozen landscape has to offer. Snow is almost impossible to photograph effectively so your only real alternative is to paint it from life. Colors must be organized for maximum effect, compositions carefully thought out and value ranges keyed for each picture.

There are some things about snow you should look for when painting; some of these things are observable but others must use constructive techniques express them in an image. Practice outdoors and trial and error are your best tools for these decisions.

There is always a slight bit of subsurface scattering going on in snow, even on overcast days, this softens transitions between light and shadow and gives the snow a tinge of the hue from whatever local color is affecting it. Where the sunlight hits snow, it spreads out in almost in a prismatic effect, the shadow areas pick up the light of the sky color and reflections from sunlit areas. Because of all of these effects snow is never pure white except where you have a direct highlight from the sun. When you are in a position to actually see the highlights, you quickly realize how much relatively darker the rest of the snow is even in the lit areas.

Different types of snow affect these properties in different ways. Snow that has been melted and refrozen looks and behaves differently than freshly fallen powder. Snow patches appear more contrasted because there is no snow around them. When there is snow everywhere, that snow has a tendency to lighten everything around it with reflected and ambient light lessening the contrast and raising the key of the painting over all. These things are observable and paintable if you are willing to get out, experience it and see it first hand for yourself.

Paintings in this article are, from top to bottom Aldro T. Hibbard,

Fritz Thaulow, Birge harrison, Isaac Levitan, Edward Redfield

John Duncan

by

Armand Cabrera

Armand Cabrera

John Duncan was born in Dundee, Scotland in 1866. At 11 years old he attended the Dundee school of art. In two years he began illustrating for local paper in Dundee. These assignments gave him an opportunity to go to London and work as a book illustrator. After three years in London Duncan felt he needed more training and wanted to leave illustration to pursue painting. He studied drawing and painting at the Antwerp School of Art in Belgium. After his instruction in Belgium Duncan toured France and Italy and viewed the great artists of the past. It was in Italy that he was most inspired by the Italian painters Botticelli and Fra Angelico.

Returning to Scotland Duncan met Patrick Geddes a biologist and educator. Geddes hired Duncan to paint his home and offered him a teaching position at a new art school Geddes was starting. When the school eventually closed Geddes secured a position in America for Duncan at the Chicago Institute starting in 1900 and lasting three years.

Duncan returned to Edinburgh and opened a studio and began working to create a unique voice with his work. He decided to incorporate Celtic themes and strive for better color and handling. He struggled to have his canvases reflect the images he saw in his mind. He disliked oil paints, which led him to experiment with other media. By 1910 he thought he had found his medium with tempera. His first large work with tempera was The Riders of the Sidhe, 45 x 69 inches.

Duncan was elected to the Scottish Royal Academy and began exhibiting in their annual shows. His studio became a gathering place for artists, writers and other Celtic Revivalists. In 1912 he married Christine Allen and the couple had two children.

At the outbreak of WW1 created financial difficulties for the artist and his family as his commissions dried up and Duncan struggled to make ends meet. His financial problems never recovered after the war and had a debilitating effect on his marriage and in 1925 his wife took his two children and left.

Duncan continued to struggle with his process and was never satisfied with the work he was producing. At times he would think his earlier work better and would go off and change his methods, only to be disappointed again.

Sales and commissions were few and his large tempera paintings were labor intensive and took him many months to complete. Geddes still gave him commissions and he still received some mural work for religious subjects but his popularity dwindled. In the 1930’s he worked with stained glass as well as his painting. In 1941 the National Gallery of Scotland in Edinburgh put on a retrospective of his work; a first for a living artist. John Duncan died in his home at the age of 79 in 1945.

Bibliography

The paintings of John Duncan A Scottish Symbolist

The paintings of John Duncan A Scottish Symbolist

John Kemplay

Pomegranate Art Books 1994

I often Despair, because my work does not improve. What I gain in one way I lose in another. Does one grow wiser with time or do some doors close as others open?

~John Duncan

Book Review: Color and Light

Review by Armand Cabrera

James Gurney hits it out of the park again with his new art instruction book Color and Light: A Guide for the Realist Painter. Following the success of his other art instruction book Imaginative Realism, which was released last year, Gurney’s new book Color and Light is filled with everything you will want to know about these two important subjects, written in a clear and concise style. This is not a step by step how to book per se but there are plenty of explanations describing the effects of color and light and how to use them in your paintings. The images accompanying the text are made up of James Gurneys own plein air paintings, figure studies and illustrations for his professional assignments. Over 300 color Illustrations and diagrams.

James Gurney hits it out of the park again with his new art instruction book Color and Light: A Guide for the Realist Painter. Following the success of his other art instruction book Imaginative Realism, which was released last year, Gurney’s new book Color and Light is filled with everything you will want to know about these two important subjects, written in a clear and concise style. This is not a step by step how to book per se but there are plenty of explanations describing the effects of color and light and how to use them in your paintings. The images accompanying the text are made up of James Gurneys own plein air paintings, figure studies and illustrations for his professional assignments. Over 300 color Illustrations and diagrams.

Beautifully printed and designed, Color and Light is sure to be considered the text on the subject for years to come. Gurney writes about this subject as a successful, professional artist. This is not someone who doesn’t make their living as a painter or some scientist who only observes but offers no practical application for his information. The paintings by Gurney are a feast for the eyes, his talent is showcased well here and you see the depth and breadth of his formidable abilities as an artist. He has included images of city scenes, portraits, landscapes, illustrations for National Geographic, magazine articles, science fiction and fantasy book covers and his own series of Dinotopia books. The sheer amount of work is amazing and you begin to understand that here is someone who loves the process of making art.

Many people know Gurney as one of the premier illustrators in the world and the author of the Dinotopia books, but for those who don’t follow his excellent blog gurneyjourney, they may be surprised to find he has always been an avid plein air painter as well. His landscapes are just as accomplished as any of his illustrations. Many of these small outdoor landscapes are showcased in this book and make up a third of the color illustrations. This is important because it is his work painted outdoors from life that infuse his real and imagined scenes with a sense of light.

Some books are considered classics in the field of art instruction; Harold Speed’s The Practice and Science of Drawing, John F Carlson’s Guide to Landscape Painting, Andrew Loomis’ Figure Drawing for all its Worth and Creative Illustration, Edgar Payne’s The Composition of Outdoor Painting, and Richard Schmid’s Alla Prima. Jim Gurney’s Color and Light is one of these books. There is no excuse for you not to buy this book, it is very reasonably priced and the wealth of information in it will help anyone interested in representational art. Whether you are a seasoned professional or Sunday hobbyist, this is the book for you.

You can order Color and Light: A Guide for the Realist Painter from the Dinotopia website where James will sign copies if requested

http://www.dinotopia.com/dinotopia-store.html

The book is also available from all the usual book retailers like Barnes and Noble, Amazon and Borders

The book is also available from all the usual book retailers like Barnes and Noble, Amazon and Borders

For more information on James Gurney visit his websites

http://jamesgurneyoriginalart.blogspot.com/More on Construction in Painting

by Armand Cabrera

I want to talk more about construction for landscape painters. Figure painters know that construction is an important aspect of their training. With figure drawing and painting you learn the ideal and then adjust and apply the specific to your understanding. This type of training rarely takes place for landscape painters. Landscape painters tend to copy what they see for good or bad. While this approach can work over time, great landscape painters, like great figure painters, understand their subject on a deeper level. Their method is partly based on observation and partly on construction. It is as much from what they know about something as it is about what they see. This combination of construction and observation helps to strengthen the painting.

Thomas Moran

Everything has an anatomy to it; understanding this underlying structure helps you paint with a more authoritative approach. Observation alone can fool the viewer into believing they are seeing something they are not. How many times have we been fooled by some foreshortened object in the landscape thinking something looks a certain way when in reality our view of it is giving us false information? If you understand the anatomy of the thing you are looking at there is little chance for confusion since you can visualize what is going on even when its shape is distorted in your view.

I want to talk more about construction for landscape painters. Figure painters know that construction is an important aspect of their training. With figure drawing and painting you learn the ideal and then adjust and apply the specific to your understanding. This type of training rarely takes place for landscape painters. Landscape painters tend to copy what they see for good or bad. While this approach can work over time, great landscape painters, like great figure painters, understand their subject on a deeper level. Their method is partly based on observation and partly on construction. It is as much from what they know about something as it is about what they see. This combination of construction and observation helps to strengthen the painting.

Thomas Moran

Everything has an anatomy to it; understanding this underlying structure helps you paint with a more authoritative approach. Observation alone can fool the viewer into believing they are seeing something they are not. How many times have we been fooled by some foreshortened object in the landscape thinking something looks a certain way when in reality our view of it is giving us false information? If you understand the anatomy of the thing you are looking at there is little chance for confusion since you can visualize what is going on even when its shape is distorted in your view.

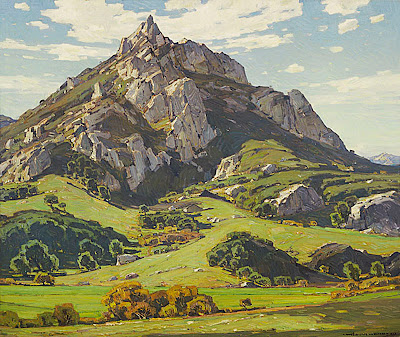

William Wendt

A constructive approach can aid the design and the elegance of your depiction too. It can help with an interpretation based only in part on naturalism. Many great painters have used their understanding of the landscape and flora and fauna to create paintings truthful to nature but utterly unique to that artist. This approach requires a thorough knowledge of the subject, the ability to pick out what’s important and strip away what isn’t. For the artist, it creates a completely personal view of the world irrespective of the subject matter.

Maynard Dixon

Observation, Construction and Visualization

by Armand Cabrera

Observational painting directly from nature opens your eyes to a world filled with color and light. There are very few situations outside that shadows aren’t filled with ambient and reflected light. Colors of local objects are affected in unusual and unpredictable ways. The organic groupings of rocks and the undulating flow of the landscape are always more interesting than imagined.

There is a drawback to observational painters though; the information is overwhelming at first. Learning to translate the 3d image of what you see is harder than copying a 2d photo. It is hard to decide what to use and what to ignore. The organic patterning of trees and other elements are hard to organize. Too many easel painters don’t transcend the observational aspects of painting. They cannot construct what they cannot copy. They lack the basic knowledge of construction to elevate their drawings past the mundane.Until they learn to visualize their compositions tend to be weak always depending on what is in front of them, whether a figure model or scene.

In the book on the biography of the Payne’s, Edgar’s daughter Evelyn remembers “He sometimes planned his studio painting in the evening; he very often sketched penciled compositions as he sat listening to the radio. They were little composition sketches, working out artistic problems. It was interesting to watch him draw; his hands moved very rapidly, and he held his Venus 6B pencil in the same fashion you would hold a piece of charcoal when drawing on canvas…” What she is talking about is construction and visualization.

A constructive approach is the one often used by comic book, illustrators and production artists. In these industries many times you learn the rules governing perspective and anatomy and construct the scenes out of your head. Color schemes follow strict rules of theory to maximize impact. Little time is spent using models under real world lighting conditions if at all.

Visualization is also used in these disciplines, creating worlds, creatures and characters from the imagination or scenes from antiquity. The skill is an important one in painting and drawing because it allows for manipulation of elements to suit the image. Artists are not tied to something observed and more focus can go toward design and composition.

The problems arise when people rely too much on these systems for a completed painting and ignore observation. A lack of understanding of how light actually works or natural effects really look can over simplify a scene. Too many illustrators ignore real world observation and use only construction and visualization for their subjects, relying solely on these skills which can never match the lighting in a real world situation. Their lighting is simplistic with the shadows too dark and their colors too saturated and color combinations monochromatic.

NC Wyeth maintained his plein air painting his whole life he incorporated impressionist observational studies into his illustrations to great success. His illustrations were painted using the places he knew giving them life.

Painting from life doesn’t just benefit the easel painter. Construction and visualization are not just good tools for the illustrator or the painter of historical subjects. Any painter serious about their painting should incorporate all three of these skills in their work. It requires a lifetime of dedication and practice.

Combining all three, visualization, construction and observation will take your art to the next level and your paintings can only improve no matter what the final use for them is.

Observational painting directly from nature opens your eyes to a world filled with color and light. There are very few situations outside that shadows aren’t filled with ambient and reflected light. Colors of local objects are affected in unusual and unpredictable ways. The organic groupings of rocks and the undulating flow of the landscape are always more interesting than imagined.

There is a drawback to observational painters though; the information is overwhelming at first. Learning to translate the 3d image of what you see is harder than copying a 2d photo. It is hard to decide what to use and what to ignore. The organic patterning of trees and other elements are hard to organize. Too many easel painters don’t transcend the observational aspects of painting. They cannot construct what they cannot copy. They lack the basic knowledge of construction to elevate their drawings past the mundane.Until they learn to visualize their compositions tend to be weak always depending on what is in front of them, whether a figure model or scene.

In the book on the biography of the Payne’s, Edgar’s daughter Evelyn remembers “He sometimes planned his studio painting in the evening; he very often sketched penciled compositions as he sat listening to the radio. They were little composition sketches, working out artistic problems. It was interesting to watch him draw; his hands moved very rapidly, and he held his Venus 6B pencil in the same fashion you would hold a piece of charcoal when drawing on canvas…” What she is talking about is construction and visualization.

A constructive approach is the one often used by comic book, illustrators and production artists. In these industries many times you learn the rules governing perspective and anatomy and construct the scenes out of your head. Color schemes follow strict rules of theory to maximize impact. Little time is spent using models under real world lighting conditions if at all.

Visualization is also used in these disciplines, creating worlds, creatures and characters from the imagination or scenes from antiquity. The skill is an important one in painting and drawing because it allows for manipulation of elements to suit the image. Artists are not tied to something observed and more focus can go toward design and composition.

The problems arise when people rely too much on these systems for a completed painting and ignore observation. A lack of understanding of how light actually works or natural effects really look can over simplify a scene. Too many illustrators ignore real world observation and use only construction and visualization for their subjects, relying solely on these skills which can never match the lighting in a real world situation. Their lighting is simplistic with the shadows too dark and their colors too saturated and color combinations monochromatic.

Painting from life doesn’t just benefit the easel painter. Construction and visualization are not just good tools for the illustrator or the painter of historical subjects. Any painter serious about their painting should incorporate all three of these skills in their work. It requires a lifetime of dedication and practice.

Combining all three, visualization, construction and observation will take your art to the next level and your paintings can only improve no matter what the final use for them is.

Top two images Edgar Payne

Bottom two images N.C. Wyeth

Daniel Urrabieta Vierge 1851-1904

by

Armand Cabrera

Armand Cabrera

Daniel Urrabieta Vierge was born in Madrid, Spain on March 5, 1851. His Father Vincent was also a professional artist and he encouraged Daniel to draw from the time he was three. Vierge was rarely without his drawing tools after that age. At thirteen he was entered into the Academy in Madrid and studied under Francisco Pradilla y Ortiz, Federico Madrazo and José Villegas Cordero. Vierge received his first assignment when he was sixteen illustrating Madrid la Nuit.

With money from his work he decided to move to Paris to study painting but the outbreak of the Franco Prussian War kept him from entering the academies there. Instead he chronicled the war and sold the illustrations to Le Monde Illustre and other periodicals. By the age of 21 he was a highly sought after illustrator of books and magazines.

With money from his work he decided to move to Paris to study painting but the outbreak of the Franco Prussian War kept him from entering the academies there. Instead he chronicled the war and sold the illustrations to Le Monde Illustre and other periodicals. By the age of 21 he was a highly sought after illustrator of books and magazines.

Vierge is considered the father of modern illustration. He worked to incorporate his illustrations into the text and he helped develop a process to copy the art directly to a plate for printing avoiding the translation of a wood engraver. This produced a line quality unique in the publishing world a the time. Vierge worked in Guache, pen and pencil. His ink work was done with a glass pen on Bristol Board. His working method was to always sketch from life, quick vignettes of everything around him. These sketchbook illustrations would be used as the basis for his professional work. He rarely used models for assignments having so much information collected over the years. His facile handling and expressive, fliud line work kept him one of the most sought after illustrators of his day.

His largest assignment was Michelet's History of France containing 1000 drawings in 26 volumes. Vierges best known work was to be Pablo De Segovia. Vierge would create 110 illustrations for the book. After completing the first 90 illustrations he had a stroke which left him paralyzed on the right side of his body, unable to draw and with short term memory loss; he was 30 years old.

Vierge spent almost ten years retraining his left hand to draw as well as he could with his right. The second edition of Pablo De Segovia had all 110 illustrations; the last twenty finished by Vierge left handed; they are indistinguishable from his earlier work. He had to have someone repeat the passages to him over and over again while he drew them because of his memory loss which eventually was cured.

In 1889 he was awarded a gold Medal at the Paris Exhibition for his work on Pablo De Segovia. His last work was the four volume set of Don Quixote, creating 75 illustrations for Cervantes Classic. Vierge never regained the use of his right hand. Daniel Vierge died at Boulogne-sur-Seine in May 1904 at the age of 53.

Google books has free complete copies of some of the books illustrated by Vierge including On the Trail of Don Quixote and Don Quixote. The books are in .pdf format complete with all of the illustration albeit in slightly fuzzy scans.

Daniel Urrabieta Vierge in the collection of the Hispanic Society of America

Elizabeth du Gué Trapier

New York, 1936

Pablo De Segovia the Spanish Sharper

Fransico De Quevedo

London 1892

Quote

Work is the greatest fun in the whole world it is the only fun I want to have.

~Daniel Vierge

And Now For Something Completely Different

As many of you already know I started my art career as an illustrator working in science fiction and fantasy. This was back in the mid eighties and before computers were tools for artists. Computer games looked like pong and pacman not like a blockbuster movie.

I still work in games and in Science Fiction and Fantasy and recently had the opportunity to contribute to a book called SciFi Art Now. John Freeman is the editor and has a blog where he is interviewing some of the artists for the book. My interview is here with a link to a download of this step by step demo in .pdf format.

My piece in the book was made digitally using my own photo reference and 3d models and combined and painted in photoshop. For this piece I painted right on the plate (photo) although this isn't always how I work digitally it is an effective tool to quickly sketchup ideas and bring them to completion. The following is the step by step process I used to make Marooned.

I started with a photo I took on a painting trip to the Sierras in Eastern California. The sandstone looked melted and gave me the idea for a crashed spaceship. I got down on the ground to shoot the small sandstone rocks from a worms eye view.

1. I separated the foreground from the sky into two layers. Using a hard brush, selecting local colors and the eraser tool I began to make the framework of the spaceship.

2. I created a third layer for my figures around a fire and established some color to get the general feel of how it will fit in the scene.

3. Next I painted some walls with portholes to make the ship seem familiar, again using the local colors in the photo to keep the sense of light.

7. I build and light the planetoids in 3ds Max and then import the images on to their own layer in Photoshop. At this point I collapse all of the layers except the figures and fire and then manipulate the colors and values to harmonize the scene. I want everything to be covered in dust to give the sense of the passage of time, unifying the color does this and I choose a color that will compliment the tones in the fire.

8. To finish the painting, I collapse the whole image and adjust the color for the figures and add more detail around them. I work all over the image fixing and adjusting where I think things need it.

I still work in games and in Science Fiction and Fantasy and recently had the opportunity to contribute to a book called SciFi Art Now. John Freeman is the editor and has a blog where he is interviewing some of the artists for the book. My interview is here with a link to a download of this step by step demo in .pdf format.

My piece in the book was made digitally using my own photo reference and 3d models and combined and painted in photoshop. For this piece I painted right on the plate (photo) although this isn't always how I work digitally it is an effective tool to quickly sketchup ideas and bring them to completion. The following is the step by step process I used to make Marooned.

I started with a photo I took on a painting trip to the Sierras in Eastern California. The sandstone looked melted and gave me the idea for a crashed spaceship. I got down on the ground to shoot the small sandstone rocks from a worms eye view.

1. I separated the foreground from the sky into two layers. Using a hard brush, selecting local colors and the eraser tool I began to make the framework of the spaceship.

2. I created a third layer for my figures around a fire and established some color to get the general feel of how it will fit in the scene.

3. Next I painted some walls with portholes to make the ship seem familiar, again using the local colors in the photo to keep the sense of light.

4. I continue to add more hard edges and machine like shapes and establish a horizon line with mountains in the distance.

5. I rough in the figures around the fire on another layer. I paint them all in warm hues so they will stand out against the rest of the scene. I make one figure female and the two sitting figures male to create a subliminal tension for the scene. Next I created a sky gradient on another layer. This will be my basis for the stars and planetoids that come next.

6. I create stars by using the noise filter then selecting a limited color range and copying and flipping the selection. I do this a couple of times adding a layer each time and make a color pass over each version to vary the look of the star field. The last thing I do is go in and hand paint selected stars with the airbrush tool before collapsing the layers back down.

7. I build and light the planetoids in 3ds Max and then import the images on to their own layer in Photoshop. At this point I collapse all of the layers except the figures and fire and then manipulate the colors and values to harmonize the scene. I want everything to be covered in dust to give the sense of the passage of time, unifying the color does this and I choose a color that will compliment the tones in the fire.

8. To finish the painting, I collapse the whole image and adjust the color for the figures and add more detail around them. I work all over the image fixing and adjusting where I think things need it.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)